District Heating is a method which, rightly so, is becoming more relevant in today’s climate. Following the update of the Housing SPG, reflecting the alterations to the London Plan, it is mandatory to assess the feasibility of District Heating, to assist towards proposed Zero Carbon residential developments.

District Heating is the supply of heat and hot water to numerous buildings from a central heat source, via a network of highly insulated pipes. It can be used to supply heat to new or existing buildings, from residential to offices or public buildings. Varying in size from covering a whole city, to serving a single apartment block.

Whilst District heating is a relatively new concept to some people in the UK, it is a system which is thriving in Europe. Copenhagen district heating system, deriving from ten CHP plants and 1650km of pipework, is supplying 98% of the city’s heating needs. Throughout Scandinavia it is a common place method, and their power stations offer up to 90% efficiency, far ahead of UK’s best cogeneration schemes. It is also a popular heating method in various other countries throughout Europe.

It did become popular in the United Kingdom after World War II, to heat the emerging large residential estates devastated during the Blitz. The Pimlico District Heating Undertaking became operational in 1950, initially supplying 1,600 social housing units with heat produced from Battersea Power Station. Despite the Power Station closing decades ago, and some of the flats sold privately, the heating infrastructure remains and is still expanding today; but alas, nationwide, our use of the technology pales into insignificance compared to our European neighbours…maybe now is the time to close that gap…

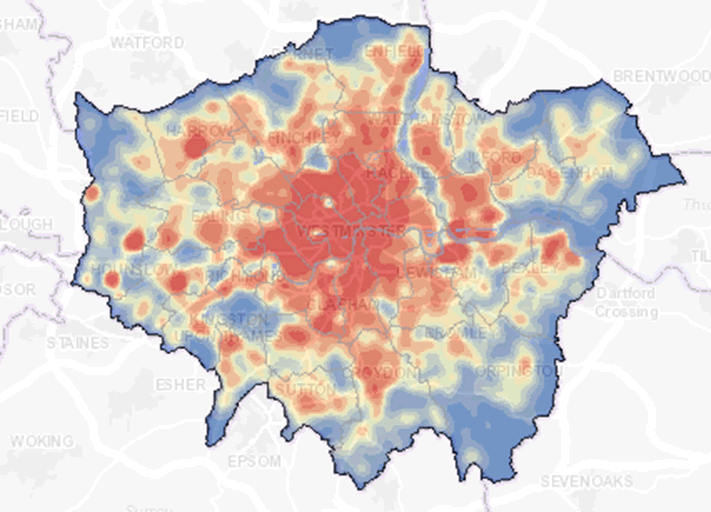

As said, if you are planning a major residential development, within the targets of the London Plan, you will have to consider district heating methods, whether connecting to an existing network, or implementing a site wide CHP, or communal heating network. The London Heat Map provides information on existing district heating systems within London, plus details for new network opportunities, and is a comprehensive tool for developers to meet the decentralised energy policy. Examples of existing heat networks in London include London King’s Cross, the Olympic Park and Stratford City, Citigen, Barkantine Heat & Power, Whitehall District Heating Network, SELCHP, the Bunnyhill energy centre, University college London and Bloomsbury networks, and the aforementioned Pimlico District Heating Undertaking.

London’s Underground system vents, supply a constant 25°C of heat all year, and this will be used in the near future, to heat a proportion of the capitals homes. This is another advantage of District heating; once the network of pipes are in place, whatever fuel source is connected at the end of the pipe to produce the heat, can adapt over time; ie replacing fossil fuels with biomass… or using the heat from the Underground.

As well as the positive environmental effect, there are economical benefits, with lower energy costs, and lower management and maintenance costs. There is however, a need for consumers to be well educated on how to get the best out of their system, including billing, communication and operation clarity. Berlin residents, for example, have long been able to request free energy saving consultations if their district energy costs are higher than average. The EU laid down requirements for informative billing in their 2012 Energy Efficiency Directive.

District Heating certainly is a step forward in helping us to become more self-sufficient, and to use locally available energy sources, rather than relying on imported fossil fuels; and with the targets set out in the London Plan, it is a step towards a lower carbon, and lower cost future.

Nick Barker – Briary Energy