This tool explains how to analyse the danger of overheating in residential projects during the design phase. It’s a pre-detail design evaluation that’s meant to help identify aspects that could contribute to or lessen the risk of overheating.

The questions can be answered either for the whole scheme or for specific units.

The accompanying guidance contains more details, including score examples and suggestions for next steps.

Guidance

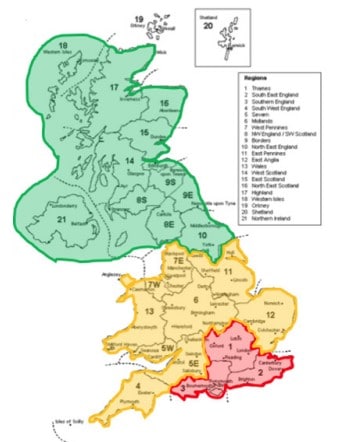

#1 Where is the scheme in the UK?

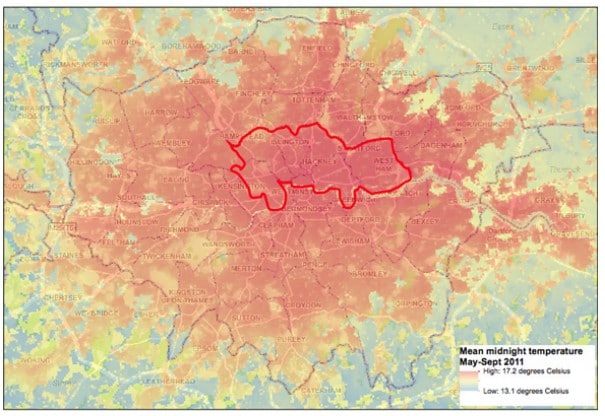

#2 Is the site likely to see an urban heat island effect?

In cities and built-up areas the preponderance of hard surfaces increases average air temperatures as these surfaces absorb solar heat during the day and release it at night. This is exacerbated by factors including heat rejection from vehicles and air conditioning equipment. This is known as the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect.

The UHI effect occurs throughout the day but is stronger at night, with night-time temperatures sometimes significantly higher than in surrounding rural locations. Higher nighttime temperatures can impact on sleep and the ability to cool building fabric.

#3 Does the site have barriers to windows opening?

Ventilation is one of the key measures to mitigate overheating risk by dissipating heat from solar and internal gains, and ideally by creating a breeze.

Ventilation is sometimes limited by the design of the window or opening. However, even if occupants can physically open windows or other openings, they are often deterred from doing so by other reasons, the main ones being:

- Noise levels: this is known to be a significant barrier to window opening, particularly in urban areas and near transport routes. The risks and possible mitigation measures should be evaluated as part of the planning application process, with advice from the project team’s acoustic consultant (if available) and the local authority’s environmental health department on site conditions and how best to balance the needs for ventilation, temperature management and acoustics. See references for further guidance, including the emerging guidance from the Association of Noise Consultants on this issue.

- Poor air quality/smells: this should be evaluated as part of the planning application process, with advice from the project team’s air quality consultant (if available) and the local authority’s environmental health department. While poor air quality as such may not necessarily change people’s behaviour to window opening, smells from neighbouring uses such as busy roads, car park areas, factories, or commercial kitchens, could.

- Security risks/crime: this should be assessed as part of the planning application process, with advice from the local security officer or police force where there are concerns. Lower floors are likely to be more susceptible. Thought should be given to whether occupants would feel safe leaving their windows open, particularly at night when sleeping, or day-time when they are not in that room.

- Health and safety: concerns by residents which might restrict how they use openings in practice should be considered e.g. risk of falling from higher floors; strong winds in high-rise buildings making it difficult to open windows safely; fear of small children escaping from openings on ground floors or through patio doors to balconies (especially in non-master bedrooms, which may be used for children and therefore not left open at night).

- Directly adjacent heat rejection plant: in cases where heat rejection plant is located near window openings, this may prevent residents from opening their windows due to noise issues and/or resulting increases in local air temperatures. The presence of heat rejection plant should also be taken into account in the location of mechanical air inlets.

These considerations are often different during the day and at night, hence the approach to scoring for this question.

In the case of noise, an acoustician and/or environmental health officer should be involved to advise on how to score this question. For example, in reference to the AVOG (Acoustics, Ventilation and Overheating Residential Design Guide published by the Association of Noise Consultants) guidance illustrated in Figure #3-2, they should advise which Level 1 assessment risk category the scheme falls under, and therefore the appropriate score for day-time and for night-time e.g. 8 points for the “high” and for the high end of the “medium“ risk categories (as defined by AVOG), 4 points for the lower part of “medium” and 0 points where acoustic risk is defined as “low”.